Hydrotherapy for Chronic Pain and Inflammation: What the Research Actually Shows

- A 2022 randomised clinical trial published in JAMA Network Open found that aquatic exercise reduced chronic low back pain more than standard physical therapy — with 54% of aquatic participants achieving clinically meaningful pain reduction at 12 months vs. 21% in the physical therapy group (Peng et al., 2022).

- A 2023 systematic review of 32 RCTs (2,200 participants) confirmed aquatic exercise significantly reduces pain and improves physical function across chronic musculoskeletal conditions, including when compared directly to land-based exercise (Shi et al., 2023).

- Warm water immersion works through three mechanisms: buoyancy reduces joint loading by 60–75%, hydrostatic pressure reduces swelling and improves circulation, and thermal transfer at 33–36°C decreases muscle spasm and blocks pain signals.

- The evidence is strongest for osteoarthritis, chronic low back pain, and fibromyalgia. It is moderate for rheumatoid arthritis and neurological conditions. It is limited for acute inflammation.

- Hydrotherapy does not cure chronic pain conditions — it reduces symptoms, improves function, and allows exercise that would otherwise be too painful on land.

Why Chronic Pain Responds to Water

Chronic pain is not just about tissue damage. In most long-term pain conditions, the nervous system itself becomes sensitised — amplifying pain signals even when the original injury has healed. This is why treatments that only target the injury site often fail: the problem has moved upstream to how the brain and spinal cord process pain.

Water addresses this from multiple angles simultaneously, which is why it works when single-modality treatments do not.

The three physical mechanisms

1. Buoyancy offloads your joints. At chest depth, water supports 60–75% of your body weight (Harrison et al., 1992). A person weighing 80 kg effectively weighs 20–30 kg in the pool. This makes movement possible when it would be excruciating on land — particularly for people with osteoarthritis, herniated discs, or post-surgical stiffness.

2. Hydrostatic pressure reduces swelling. The water exerts even pressure on all submerged tissue, compressing fluid out of inflamed joints and soft tissue back into circulation. This is the same principle as compression stockings, but applied uniformly across the entire body. The result is measurable — limb volume decreases during immersion sessions.

3. Warm water blocks pain signals. At therapeutic temperatures (33–36°C), warm water activates thermal receptors in the skin that compete with pain signals for attention at the spinal cord level — a process called gate control. Mooventhan and Nivethitha (2014) documented that water temperature and pressure “block nociceptors by acting on thermal receptors and mechanoreceptors,” producing analgesia without medication.

The exercise advantage

The mechanisms above explain why simply sitting in warm water provides temporary relief. But the real clinical value comes from combining these effects with active exercise. When you move in warm water, you get pain relief and joint offloading that allow you to exercise at intensities you could not tolerate on land. Over weeks, this builds strength, improves range of motion, and reduces disability — effects that last after you leave the pool.

This is the difference between a warm bath (passive, temporary) and a hydrotherapy programme (active, progressive, lasting).

The Evidence by Condition

Chronic low back pain — strong evidence

Chronic low back pain has the most robust aquatic therapy evidence of any condition. The landmark study is Peng et al. (2022), a randomised clinical trial published in JAMA Network Open with 113 participants:

- Participants did 24 sessions of aquatic exercise (60 minutes, twice weekly for 3 months) or received standard physical therapy modalities

- At 12 months, the aquatic group showed a −2.04 point additional reduction in most severe pain compared to physical therapy

- 53.6% of aquatic participants met clinically meaningful pain improvement vs. 21.1% in the physical therapy group

- 46.4% achieved meaningful disability improvement vs. 7.0% in the control group

- 92.9% of aquatic participants recommended their treatment

A separate controlled trial found aquatic therapy improved low back pain by 3.83 points on a visual analogue scale and disability by 12.7 points on the Oswestry Disability Index — both clinically significant improvements (Dundar et al., 2009).

A 2023 hot spring hydrotherapy meta-analysis of 16 studies (1,656 participants) found significant reductions in pain intensity and functional disability, with effects most pronounced in adults over 60 (Bai et al., 2023).

Knee osteoarthritis — strong evidence

A 2024 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs in the International Journal of Surgery found hydrotherapy significantly reduced knee osteoarthritis pain at every measured timepoint (Lei et al., 2024):

- 1 week: statistically significant pain reduction (P = 0.001)

- 4 weeks: sustained improvement (P = 0.030)

- 8 weeks: largest effect observed (P < 0.001)

- Functional scores (WOMAC) improved at all timepoints

- No serious adverse events in any hydrotherapy participant

The progressive improvement over 8 weeks matters. It suggests the benefit is not just pain masking — structural adaptation (stronger muscles, better joint mechanics) is occurring.

Fibromyalgia — strong evidence

Fibromyalgia responds particularly well to aquatic therapy because the condition involves widespread pain sensitisation that makes land-based exercise intolerable for many patients.

Mooventhan and Nivethitha (2014) cited a systematic review describing “strong evidence for the use of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome,” with improvements in pain, tender point count, and overall health status. Combined sauna and underwater exercise over 12 weeks produced “significant reduction” in pain and improved quality of life.

A 2024 RCT comparing aquatic therapy to land-based therapy for women with fibromyalgia found aquatic therapy was superior for reducing pain intensity and improving sleep quality after 6 weeks.

Rheumatoid arthritis — moderate evidence

The evidence for rheumatoid arthritis is positive but less extensive than for osteoarthritis. Warm water reduces morning stiffness and joint pain, and the buoyancy allows exercise during flares when land-based movement would increase inflammation. However, during acute inflammatory flares with hot, swollen joints, warm water immersion may not be appropriate — cold water or rest may be preferable. Discuss timing with your rheumatologist.

Neurological conditions — moderate evidence

Aquatic exercise for multiple sclerosis patients improved pain, spasms, disability, fatigue, and depression over a 40-session programme (Mooventhan & Nivethitha, 2014). For Parkinson’s disease, a 2023 systematic review found hydrotherapy significantly improved balance function. The water provides a safe environment for movement practice — a fall in the pool is not a fall on a hard floor.

Hydrotherapy and Inflammation: What the Science Supports (and What It Does Not)

Many hydrotherapy articles claim it “reduces inflammation.” This requires a more careful explanation.

What is supported:

- Hydrostatic pressure reduces oedema. The mechanical compression of water pushes excess fluid out of swollen tissue. This is a physical effect, not a biochemical anti-inflammatory action. It reduces the visible signs of inflammation (swelling) without directly altering the inflammatory cascade.

- Exercise reduces systemic inflammation over time. Regular exercise — including aquatic exercise — lowers circulating levels of inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6) over weeks to months. This is an indirect anti-inflammatory effect mediated by improved metabolic health and reduced body fat, not a direct property of water.

- Cold water immersion suppresses acute inflammatory markers. Cold exposure at 10–15°C elevates norepinephrine, which inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines. A 2024 network meta-analysis of 57 studies confirmed cold water immersion reduces post-exercise muscle oedema and inflammation (Li et al., 2024). However, some researchers argue that suppressing the acute inflammatory response may delay tissue repair.

What is not well supported:

- Warm water directly reducing inflammatory cytokines. The evidence for warm water immersion lowering systemic inflammatory markers is limited. Warm water lowers cortisol and improves subjective wellbeing, but the direct biochemical anti-inflammatory effect is not well established in current research.

- Hot tubs or spas treating inflammatory diseases. There is no good evidence that recreational spa use treats conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease at a disease-modifying level.

The honest summary: hydrotherapy manages the consequences of inflammation (pain, swelling, stiffness, reduced mobility) better than it treats the underlying inflammatory process itself. For disease-modifying treatment of inflammatory conditions, you need medication. Hydrotherapy complements that — it does not replace it.

What a Hydrotherapy Session for Chronic Pain Looks Like

If you have never been to a hydrotherapy pool, here is what to expect in a typical physiotherapist-led session:

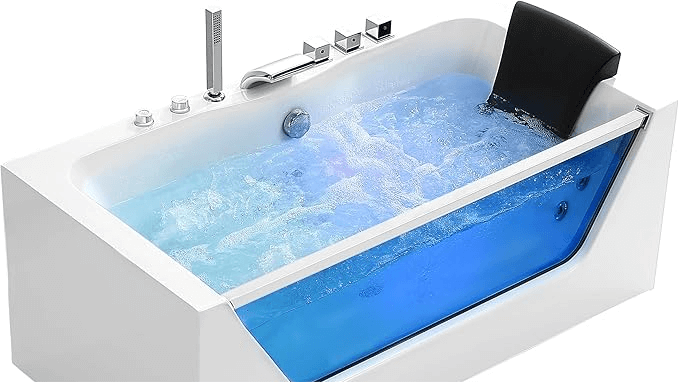

Setting: A small pool (not a swimming pool), heated to 33–36°C, with a depth of 1.0–1.4 metres. The room is warm and humid. You will be in swimwear.

Duration: 30–45 minutes in the water, plus time to change before and after.

Structure:

- Warm-up (5 minutes): Walking in the pool, gentle arm and leg movements to acclimatise

- Targeted exercises (20–30 minutes): Stretches, resistance movements against the water, balance work, and specific exercises for your condition. The physiotherapist adapts these to your pain levels in real time

- Cool-down (5 minutes): Slow walking, floating, or gentle stretching

Frequency: Most programmes run 2–3 sessions per week for 6–12 weeks. The Peng et al. (2022) trial used twice weekly for 12 weeks (24 sessions total) and showed benefits lasting to 12 months.

What you will feel: Many people notice reduced pain during and immediately after the session. Lasting improvement in function typically appears after 3–4 weeks of consistent sessions. Some people feel temporarily more tired after the first few sessions — this is normal and settles within a week or two.

Who Should and Should Not Use Hydrotherapy for Pain

Good candidates

- Chronic low back pain that has not responded well to land-based physiotherapy

- Osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, or spine — especially if you struggle with weight-bearing exercise

- Fibromyalgia — particularly if land-based exercise triggers symptom flares

- Post-surgical rehabilitation (once wounds are fully healed)

- Chronic pain with obesity — water supports your weight while you build fitness

- Elderly patients with multiple pain sites and fall risk

Contraindications — do not use if you have:

- Open wounds, skin infections, or unhealed surgical incisions

- Uncontrolled epilepsy

- Severe cardiovascular disease or unstable blood pressure (the hydrostatic pressure and warmth affect your circulation)

- Active urinary tract or chest infections

- Chlorine allergy or severe skin conditions aggravated by pool chemicals

- Fear of water that cannot be managed with graded exposure (this is more common than people admit — mention it to your therapist)

How to Access Hydrotherapy

NHS (UK): Ask your GP for a physiotherapy referral and specifically request aquatic therapy. Availability varies by area — some NHS trusts have hydrotherapy pools; others do not. Waiting times can be long.

Private physiotherapy: Many private physio clinics offer hydrotherapy sessions at £40–80 per session. Some health insurance plans cover it with a GP or consultant referral.

Local pools with warm water: Some public leisure centres have warm water or teaching pools at 30–33°C. These are not hydrotherapy pools, but the warmer temperature still provides buoyancy and thermal benefits for self-directed exercise.

At home: A warm bath (35–37°C) provides hydrostatic pressure and thermal effects for your lower body. It is not a substitute for guided aquatic exercise, but it is free and useful for pain flares between sessions.

The Bottom Line

Hydrotherapy works for chronic pain — not as a cure, but as one of the most effective ways to reduce symptoms and improve function. The evidence is particularly strong for chronic low back pain (where aquatic exercise outperformed standard physiotherapy at 12 months), osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia.

The “inflammation” claim needs qualifying. Hydrotherapy manages the consequences of inflammation — swelling, stiffness, pain, reduced mobility — rather than treating the inflammatory process itself. If you have an inflammatory condition, you still need your medication. Hydrotherapy complements it.

If you have been struggling with chronic pain and land-based exercise makes it worse, aquatic therapy is worth trying. Ask your doctor for a referral to a physiotherapist with hydrotherapy access.

References

- Peng, M-S. et al. (2022). Efficacy of therapeutic aquatic exercise vs physical therapy modalities for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2142069. PMC8742191

- Shi, Z. et al. (2023). Efficacy of aquatic exercise in chronic musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 18, 906. DOI link

- Lei, C. et al. (2024). The efficacy and safety of hydrotherapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Surgery. PubMed

- Li, J. et al. (2024). The effects of hydrotherapy and cryotherapy on recovery from acute post-exercise induced muscle damage — a network meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 25, 724. PMC11409518

- Mooventhan, A. & Nivethitha, L. (2014). Scientific evidence-based effects of hydrotherapy on various systems of the body. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(5), 199–209. PMC4049052

- Harrison, R.A., Hillman, M. & Bulstrode, S. (1992). Loading of the lower limb when walking partially immersed. Physiotherapy, 78(3), 164–166.

- Bai, R. et al. (2023). The impact of hot spring hydrotherapy on pain perception and dysfunction severity in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PubMed

Last reviewed: February 2026. This article is for informational purposes and does not replace medical advice. Consult a qualified healthcare professional before starting any hydrotherapy programme.

]]>