Every Hydrotherapy Product Ranked by Evidence: From Strongest Research to Zero Proof

There are dozens of products marketed under the “hydrotherapy” label. Some have decades of clinical research behind them. Others have none. This article ranks every major category from strongest evidence to weakest, so you can see at a glance where your money is well spent and where it is wasted.

The rankings are based on the volume and quality of published research — primarily systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) indexed in PubMed. Products with multiple high-quality reviews rank higher than those with only a few small studies or no published evidence at all.

Key Takeaways

- Aquatic exercise in warm water has the strongest evidence of any hydrotherapy intervention — 32 RCTs with 2,200 participants for musculoskeletal conditions alone (Shi et al., 2023)

- Simple warm water immersion at 40–42.5°C has strong evidence for sleep improvement (Haghayegh et al., 2019 — 17 studies) and moderate evidence for pain relief

- Hot and cold packs have moderate evidence from a network meta-analysis of 59 studies (Fang et al., 2021)

- Bath additives (Epsom salts, essential oils) have weak or contested evidence — the warm water itself accounts for most observed benefits

- Products claiming “detoxification,” “cellular regeneration,” or “immune boosting” have zero clinical evidence

The Evidence Hierarchy: How These Rankings Work

Not all research is equal. A single small study with 12 participants does not carry the same weight as a meta-analysis combining data from 2,200 people across 32 trials. Here is the hierarchy used in these rankings, from strongest to weakest:

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs — The gold standard. Combines results from multiple controlled studies to identify consistent patterns.

- Individual RCTs — Controlled experiments comparing a treatment group to a control group. Good evidence, but a single trial can be a fluke.

- Observational studies and cohort studies — Show associations but cannot prove cause and effect.

- Case reports and expert opinion — The weakest form of evidence. Useful for generating hypotheses, not for making treatment decisions.

- No published research — The product’s claims are based entirely on marketing, tradition, or plausible-sounding mechanisms that have never been tested.

Tier 1: Strong Evidence (Multiple Systematic Reviews)

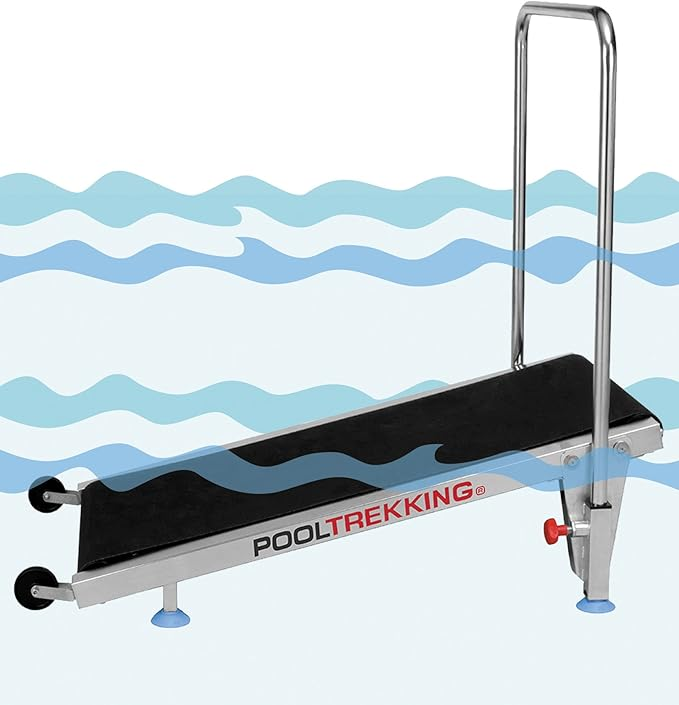

Aquatic exercise equipment (used in warm water pools)

Evidence: 5+ systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Aquatic exercise — performing structured exercises in warm water using resistance equipment — has the broadest and deepest evidence base of any hydrotherapy intervention. A 2023 meta-analysis of 32 RCTs with 2,200 participants found aquatic exercise improved pain, physical function, and quality of life in chronic musculoskeletal conditions compared to no exercise (Shi et al., 2023). A separate meta-analysis found it significantly reduced pain in knee osteoarthritis at 1, 4, and 8 weeks (Wang et al., 2023). A 2024 review found it improved physical performance in older adults.

Crucially, when compared directly to land-based exercise, aquatic exercise provided superior pain relief in some studies — making it one of the few hydrotherapy interventions that outperforms its non-water equivalent.

Products: Aqua dumbbells (£10–£30), resistance bands (£8–£25), aqua jogging belts (£15–£40), flotation aids (£5–£15). Requires pool access (public pools: £3–£8/session).

Limitation: The strong evidence comes from supervised, structured programmes — not from casually bobbing in a pool. Inadequate resistance application is a documented reason aquatic exercise sometimes fails to produce results.

Warm water immersion (bathtubs, hot tubs)

Evidence: 3+ systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Passive warm water immersion at 40–42.5°C has consistent evidence for two outcomes: improved sleep and short-term pain relief. A meta-analysis of 17 studies found warm bathing 1–2 hours before bed reduced sleep onset latency by approximately 10 minutes (Haghayegh et al., 2019). A separate systematic review confirmed improvements in sleep quality through thermoregulatory mechanisms (Gholami et al., 2023). For pain, multiple reviews support warm water immersion for osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

Products: A standard bathtub (£0 if you have one), inflatable hot tubs (£300–£800), acrylic hot tubs (£3,000–£12,000), swim spas (£15,000–£35,000+).

Limitation: The evidence is for warm water itself — not for specific hot tub features. Jets, LED lighting, and Bluetooth speakers do not add therapeutic value — for a detailed explanation of why, see our guide to the physics behind hydrotherapy machines. A £300 inflatable hot tub provides identical water temperature benefits to a £15,000 acrylic model.

Tier 2: Moderate Evidence (Individual RCTs or Limited Systematic Reviews)

Hot and cold packs (contrast therapy)

Evidence: 1 network meta-analysis, 1 scoping review, multiple individual RCTs

A network meta-analysis of 59 studies (1,367 participants) found hot packs most effective within 24 hours post-exercise, cold therapy most effective beyond 48 hours, and contrast therapy (alternating hot and cold) moderately effective across timeframes (Fang et al., 2021). A 2025 scoping review confirmed benefits for pain, range of motion, and swelling (Ferrara et al., 2025).

Products: Reusable gel packs (£5–£20), hot water bottles (£5–£10), ice bags (£3–£8). Electronic contrast therapy devices (£100–£300) have no evidence of superiority over manual application.

Massage guns (percussive therapy)

Evidence: 2 systematic reviews (2023), small sample sizes

A 2023 systematic review of 13 studies (255 participants) found massage guns acutely improved strength (25% after four weeks), flexibility (all 13 studies), and reduced pain (16% reduction in back pain after two weeks) (Konrad et al., 2023). A separate review confirmed flexibility benefits (Chen et al., 2023). While not strictly hydrotherapy, massage guns target the same goals and are frequently sold alongside water-based products.

Products: Budget models (£30–£80), premium brands (£250–£500). No evidence that expensive brands outperform cheaper alternatives.

Limitation: Most studies have moderate risk of bias. Total participant count across all studies is only 255. Long-term effects are unknown.

Whirlpool baths

Evidence: Several individual RCTs, no comprehensive meta-analysis specific to home whirlpool baths

Whirlpool baths — bathtubs with built-in water jets — combine warm water immersion with pressurised massage. Individual RCTs have shown benefits for specific conditions: a blinded RCT found whirlpool therapy produced greater range of motion improvement than hot packs for distal radius fracture rehabilitation (Timmers et al., 2017). Another RCT found whole-body whirlpool hydrotherapy at 34–36°C reduced pain and anxiety in myofascial pain syndrome (Ortiz et al., 2013). An 8-week study found whirlpool baths at 40°C reduced pain and stiffness in stroke patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Products: Built-in whirlpool baths (£500–£3,000 installed), standalone Jacuzzi-style baths (£1,500–£8,000).

Limitation: Most whirlpool research comes from clinical settings with professionally calibrated equipment. Home whirlpool baths vary widely in jet pressure and configuration, so clinical results may not translate directly.

Tier 3: Weak Evidence (Plausible but Limited Research)

Foot spas (heated)

Evidence: Small studies on warm foot baths, no RCTs on commercial foot spas specifically

Warm foot baths at or below 40°C for at least 10 minutes over one week or more have shown improvements in subjective sleep quality in small studies. The mechanism is the same as full-body immersion — peripheral vasodilation promoting core temperature decline. However, commercial foot spas add vibration, rollers, and bubbles with no independent evidence that these features provide additional benefit over plain warm water.

Products: Electric foot spas (£20–£100). A bowl of warm water (£2) provides equivalent temperature exposure.

Epsom salt bath additives

Evidence: Contested, with no large RCTs confirming claimed mechanism

Epsom salts (magnesium sulphate) are widely marketed for bath use with claims about magnesium absorption through the skin. A small, unblinded University of Birmingham study (19 subjects) found plasma magnesium levels rose after seven days of bathing. However, a 2017 review in the journal Nutrients concluded that transdermal magnesium absorption is “not scientifically supported” based on available evidence, noting small sample sizes, unblinded designs, and the skin’s barrier function (Gröber et al., 2017).

A 2024 clinical trial of Epsom salt foot baths for chemotherapy-induced neuropathy showed positive results, but this was a specific clinical application, not evidence for general wellness claims.

Any benefits experienced from Epsom salt baths may be attributable to the warm water itself rather than the magnesium content.

Products: Epsom salts (£3–£15 per kg). Inexpensive regardless, but do not expect the specific benefits claimed on packaging.

Hydrotherapy shower heads and panels

Evidence: No published RCTs comparing hydrotherapy shower heads to standard showers

The warm water component provides the same thermoregulatory benefits as any warm water exposure. The “jet massage” component has a plausible connection to massage therapy evidence. However, there are no clinical trials specifically on hydrotherapy shower heads for any health outcome. Claims about “deep tissue hydro massage” from a shower head are extrapolations, not direct evidence.

Products: Hydrotherapy shower heads (£30–£150), multi-jet panels (£150–£800).

Tier 4: No Evidence (Marketing Claims Only)

Ionic detox foot baths

These devices claim to remove toxins through your feet via an electrical current. The water changes colour during use, which sellers attribute to extracted toxins. Independent testing has confirmed the colour change results from electrode corrosion — it occurs whether or not your feet are present. No clinical trials demonstrate any toxin removal. UK Trading Standards has repeatedly flagged “detox” product claims as misleading.

Magnetic or “structured” water devices

Products claiming to magnetise, alkalise, or “structure” bath water for therapeutic benefit have no scientific basis. Water cannot be magnetised in any stable way, and your body’s blood pH is tightly regulated regardless of what you bathe in.

Essential oil diffusing bath jets

While aromatherapy has some evidence for anxiety and mood (separate from hydrotherapy), bath jets specifically designed to “infuse” essential oils into water provide no proven mechanism for delivering therapeutic doses of any active compound through skin immersion. The pleasant smell may promote relaxation — but so does adding a few drops of oil to a standard bath at no extra equipment cost.

Complete Rankings Table

| Tier | Product Category | Evidence Quality | UK Price Range | Key Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Strong) | Aquatic exercise equipment | 5+ systematic reviews | £10–£40 + pool access | Shi et al. 2023 (32 RCTs, 2,200 patients) |

| 1 (Strong) | Warm water immersion (baths/hot tubs) | 3+ systematic reviews | £0–£12,000 | Haghayegh et al. 2019 (17 studies) |

| 2 (Moderate) | Hot and cold packs | 1 meta-analysis + reviews | £5–£20 | Fang et al. 2021 (59 studies, 1,367 patients) |

| 2 (Moderate) | Massage guns | 2 systematic reviews | £30–£500 | Konrad et al. 2023 (13 studies, 255 patients) |

| 2 (Moderate) | Whirlpool baths | Several individual RCTs | £500–£8,000 | Timmers et al. 2017; Ortiz et al. 2013 |

| 3 (Weak) | Heated foot spas | Small studies only | £20–£100 | Warm footbath sleep studies |

| 3 (Weak) | Epsom salt additives | Contested | £3–£15 | Gröber et al. 2017 (sceptical review) |

| 3 (Weak) | Hydrotherapy shower heads | No direct RCTs | £30–£800 | None specific |

| 4 (None) | Ionic detox foot baths | Zero evidence | £50–£200 | Debunked |

| 4 (None) | Magnetic water devices | Zero evidence | £30–£150 | No scientific basis |

How to Use This Ranking When Shopping

This evidence hierarchy serves a practical purpose. When considering any hydrotherapy purchase, follow these steps:

Step 1: Identify which tier the product falls into. If it is Tier 4, do not buy it. If it is Tier 3, understand that you are paying for a product whose specific claims are unproven — the warm water may help, but the product’s unique features likely add nothing.

Step 2: Compare within the tier. In Tier 1, aquatic exercise equipment costs £10–£40 while hot tubs cost £300–£12,000. Both have strong evidence, but the equipment is dramatically cheaper (assuming you have pool access).

Step 3: Check whether the cheapest option in the tier covers your need. For Tier 1 warm water immersion, a standard bathtub provides identical thermoregulatory benefits to a £12,000 hot tub. For Tier 2 temperature therapy, £5 gel packs perform equivalently to £300 electronic devices.

Step 4: Only upgrade when a cheaper option has proven insufficient. If you genuinely use warm water immersion nightly and find refilling a bathtub impractical, a hot tub that maintains temperature is a justified upgrade. If you use hot/cold packs daily and find manual application cumbersome, an electronic device might be worth it. But start cheap and upgrade based on actual experience, not marketing promises. For a goal-based decision framework that maps therapeutic needs to equipment, see our evidence-based equipment guide.

Brand Names Do Not Change the Evidence

Brands like Jacuzzi, Kohler, and American Standard make well-built products. But brand reputation relates to manufacturing quality, durability, and customer service — not to superior therapeutic effects. A Jacuzzi hot tub heats water to the same temperature as any other hot tub. The research supporting warm water immersion does not differentiate between brands.

When choosing between brands, consider:

- Build quality and insulation — Better insulation means lower running costs, not better therapy

- Warranty and after-sales support — Important for expensive purchases like hot tubs

- UK safety certification — Ensure UKCA or CE marking on all electrical products

- Spare parts availability — Cheaper brands may lack replacement components after a few years

What you should not pay a premium for is claims of proprietary therapeutic technology. “PowerPro Hydro Jets” and “ThermaFlow Massage Systems” are marketing names for water pumps and nozzles. The therapeutic mechanism is water temperature and pressure — physics that does not vary by brand. For more on spotting misleading claims when shopping online, see our sceptical guide to buying hydrotherapy products.

What No Hydrotherapy Product Can Do

- Detoxify your body — Your liver and kidneys handle this. No bath, soak, or device supplements or replaces their function.

- Cure any disease — Hydrotherapy manages symptoms (pain, stiffness, poor sleep). It does not cure arthritis, fibromyalgia, or any chronic condition.

- Boost your immune system — The immune system is not a dial. Warm water does not increase immune function.

- Replace medical treatment — If your GP has prescribed physiotherapy, medication, or surgery, a hot tub is not a substitute.

- Cause weight loss — Sitting in warm water does not burn meaningful calories. Aquatic exercise burns calories because it is exercise, not because it involves water.

For a data-driven look at what clinical trial participants actually report about hydrotherapy outcomes — versus marketing testimonials — see our analysis of hydrotherapy tub research outcomes.

Related Reading

- How Hydrotherapy Machines Actually Work: The Physics Behind Every Claim

- Hydrotherapy Equipment: An Evidence-Based Decision Framework

- Home Hydrotherapy Equipment: What Works vs Marketing Fantasy

- What Research Participants Actually Report About Hydrotherapy Tubs

References

- Shi, Z. et al. (2023). Efficacy of aquatic exercise in chronic musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 18, 917. PubMed

- Wang, H. et al. (2023). The efficacy and safety of hydrotherapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Rehabilitation. PubMed

- Haghayegh, S. et al. (2019). Before-bedtime passive body heating by warm shower or bath to improve sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 46, 124–135. PubMed

- Gholami, M. et al. (2023). Efficacy of hydrotherapy, spa therapy, and balneotherapy on sleep quality: a systematic review. International Journal of Biometeorology. PubMed

- Fang, Y. et al. (2021). Effect of cold and heat therapies on pain relief in patients with delayed onset muscle soreness: A network meta-analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 53(11). PubMed

- Ferrara, P.E. et al. (2025). Mechanisms and Efficacy of Contrast Therapy for Musculoskeletal Painful Disease: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(5), 1441. PubMed

- Konrad, A. et al. (2023). The Effect of Percussive Therapy on Musculoskeletal Performance and Experiences of Pain: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 18(2). PubMed

- Chen, J. et al. (2023). The Effects of Massage Guns on Performance and Recovery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 8(3), 138. PMC

- Timmers, T. et al. (2017). The Effect of Therapeutic Whirlpool and Hot Packs on Hand Volume During Rehabilitation After Distal Radius Fracture. Journal of Hand Therapy, 30(4), 416–423. PubMed

- Gröber, U. et al. (2017). Myth or Reality—Transdermal Magnesium? Nutrients, 9(8), 813. PMC